## Uncomment for colab users

# !pip install amtutorialEnergy Transformer

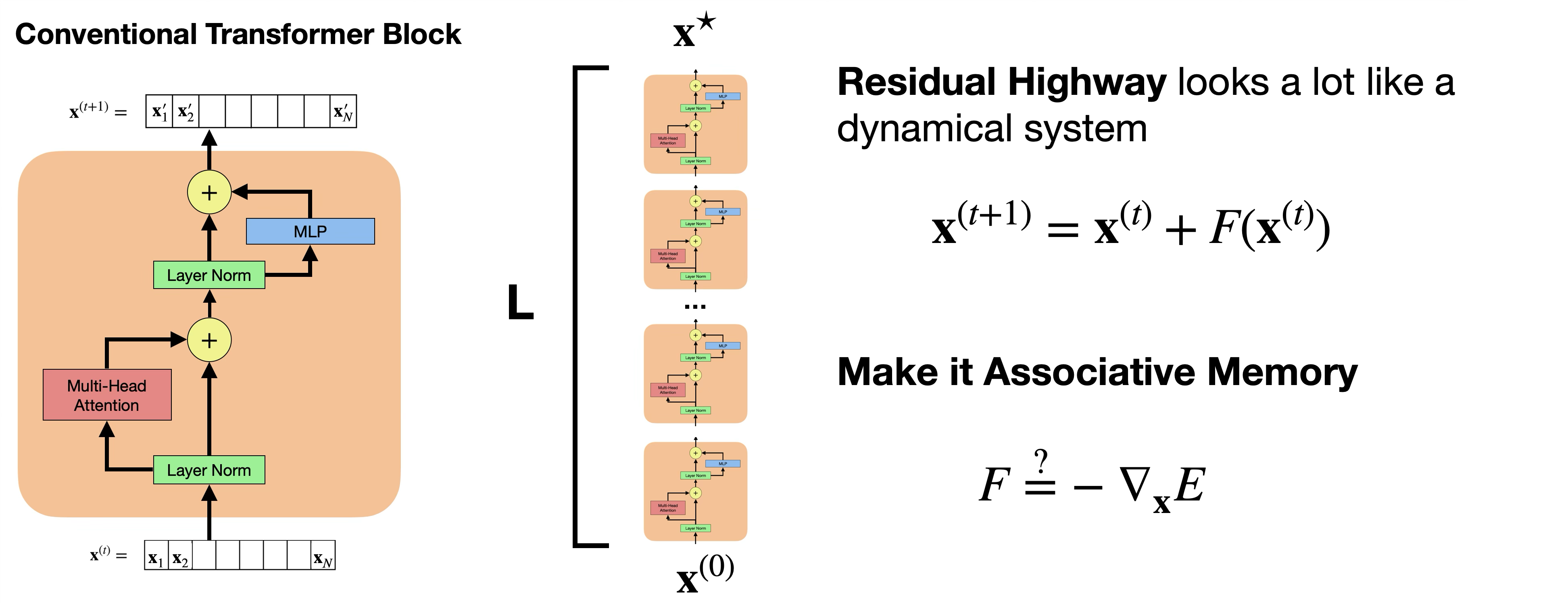

Flow perspective of Transformers

Squint, and the Transformer looks like a dynamical system.

At its core, the transformer is a stack of \(L\) transformer blocks that takes a length \(N\) sequence of input tokens \(\{\mathbf{x}^{(0)}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{x}^{(0)}_N\}\) and outputs a length \(N\) sequence of output tokens \(\{\mathbf{x}^{(L)}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{x}^{(L)}_N\}\). Each token \(\mathbf{x}^{(l)}_i \in \mathbb{R}^D\) is a vector of dimension \(D\).

When blocks are stacked, the residual connections form a “residual highway” that consists entirely of normalizations and additions from Attention and MLP operations.

Associative Memory (AM) requires a global energy function, where each computation minimizes the total energy of the system. Our goal is to derive an energy function whose gradient looks as much like the Transformer block as possible.

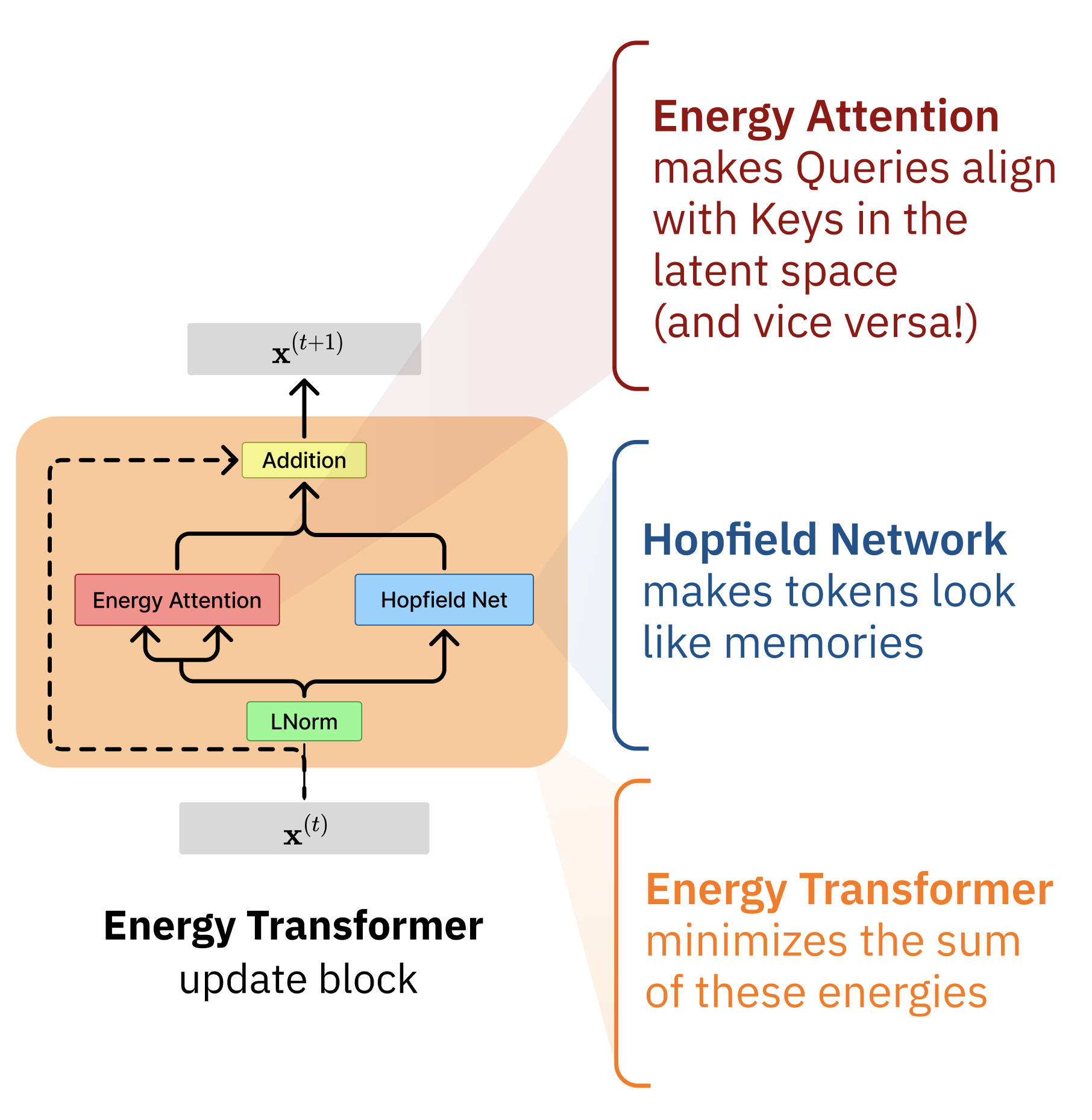

Introducing Energy into the Transformer

We will now build a kind of associative memory called the “Energy Transformer” [1] that turns the familiar transformer operation into an energy minimization. Energy Transformer (ET) defines a single energy on an \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times D}\) collection of tokens, where we can think of each token \(\mathbf{x}_B\) as a “particle” that knows some information about itself and needs to figure out what it should become. Some particles (unmasked tokens) already know their identity, while others (masked tokens) only know their position and must discover their identity by interacting with their neighbors.

Minimizing the energy of the Energy Transformer (ET) is a recurrent process. The entire transformer consists of a single Transformer block, and each “layer” of the transformer becomes a gradient descent step down the energy. This gradient descent step looks remarkably like a standard transformer block, complete with attention, MLP-like operations, layer normalizations, and residual connections.

The global energy combines two intuitive ideas: (1) attention energy that encourages masked tokens to align with relevant unmasked tokens, and (2) memory energy that ensures all tokens look like realistic patterns the model has learned. The gradient of each of these energies look like a self-attention and MLP, respectively, with some shared weight constraints.

This is one of those situations where the code ends up being significantly simpler than the equations. We write the equations for completeness, but feel free to skip to Section 2.3 for succinct code.

Attention Energy

We describe the energy of a multi-headed attention with \(H\) heads, where the \(h\)-th head of attention is parameterized by \(\mathbf{W}_h^Q, \mathbf{W}_h^K \in \mathbb{R}^{D \times Y}\), where \(Y\) is the “head dimension”. The input to the attention is the normalized token vectors \(\hat{\mathbf{x}} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times D}\). In the math that follows, we index the heads by \(h=1\ldots H\), the head dimension by \(\alpha=1\ldots Y\), tokens by \(A,B,C=1 \ldots N\), and each token vector by \(i,j=1\ldots D\).

We find it convenient to use Einstein notation for the math, since it maps 1:1 to the einops operations we’ll use in the code. If you aren’t familiar with the notation, check out this awesome tutorial. But fair warning, the equations at first look pretty complicated with all the indices.

One tip for reading equations with lots of indices: you don’t need to remember the shape or order of tensors, just remember the meaning of the indices. The number of subscripts is the number of dimensions of the tensor, and the meaning of each dimension is captured in the index name. For example, let \(B=1\ldots N\) index the token position in a sequence, and let \(i=1\ldots D\) index into each token vector. \(x_{Bi}\) is an element of a 2-dimensional tensor capturing the sequence length \(N\) and token dimension \(D\). Transposes don’t have meaning since things are named, so \(x_{Bi} = x_{iB}\). So long as you know the index semantics, you can read always read the equation. Everything is just scalar multiplication and addition.

The familiar queries and keys are computed as normal linear transformations:

\[ \begin{split} K_{h \alpha B} &= \sum\limits_j W^K_{h \alpha j}\; \hat{x}_{Bj}, \qquad \mathbf{K} \in \mathbb{R}^{H \times Y \times N} \\ Q_{h \alpha C} &= \sum\limits_j W^Q_{h \alpha j}\; \hat{x}_{Cj}, \qquad \mathbf{Q} \in \mathbb{R}^{H \times Y \times N} \end{split} \]

Our familiar “raw attention scores” (pre-softmax) are still the dot-product correlations between each query and key:

\[ A_{hBC} = \sum_{\alpha} K_{h\alpha B} Q_{h\alpha C} \]

Now for the different part: we describe the energy of the attention as the negative log-sum-exp of the attention scores. We will use the \(\beta\) as an inverse-temperature hyperparameter to scale the attention scores.

\[ E^\text{ATT} = -\frac{1}{\beta} \sum_{h=1}^H \sum_{C=1}^N \log \left( \sum_{B \neq C} \exp(\beta A_{hBC}) \right) \tag{1}\]

As we saw in a previous notebook, the negative log-sum-exp is an exponential variation of the Dense Associative Memory. The cool thing is that the gradient of the negative log-sum-exp is the softmax, which is what we’d like to see in the attention update rule.

You may recall that traditional attention also has a value matrix. When we take the gradient of Equation 1, we lose the flexibility to include an independently parameterized values: the values must be a function of the queries and the keys.

Memory Energy

In traditional transformers, the MLP (without biases) can be written as a two-layer feedforward network with a ReLU on the hidden activations. The MLP is parameterized by two weight matrices \(\mathbf{V}, \mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times D}\) where \(M\) is the size of the hidden layer (\(M=4D\) is often viewed as the default expansion factor atop token dimension \(D\)). Let’s again use Einstein notation, where \(\mu=1\ldots M\) indexes the hidden units, \(i,j=1\ldots D\) index the token dimensions, and \(B=1\ldots N\) indexes each token.

\[ \text{MLP}(\hat{\mathbf{x}})_{Bi} = \sum_\mu W_{\mu i} \; \text{ReLU}\left(\sum_j V_{\mu j} \hat{\mathbf{x}}_{Bj}\right) \tag{2}\]

If we assume weight sharing between \(\mathbf{V} = \mathbf{W} = \boldsymbol{\xi}\), this is a gradient descent step down the energy of a Hopfield Network

\[ E^{\text{HN}}(\hat{\mathbf{x}}) = - \sum_{B, \mu} F\left(\sum_j \xi_{\mu j} \hat{\mathbf{x}}_{Bj}\right) \]

with rectified quadratic energy \(F(\cdot) := \frac12 \text{ReLU}(\cdot)^2\). If we say \(f(\cdot) := F'(\cdot) = \text{ReLU}(\cdot)\), the negative gradient of the energy is

\[ -\frac{\partial E^{\text{HN}}(\mathbf{\hat{x}})}{\partial \hat{x}_{Bi}} = \sum_\mu \xi_{\mu i} \; f\left(\sum_j \xi_{\mu j} \hat{\mathbf{x}}_{Bj}\right), \]

which is identical to the MLP operation in Equation 2 with a weight sharing constraint.

It is perfectly reasonable to consider other convex functions \(F\) for use in the energy. Polynomials of higher degree \(n\) or exponential functions are both valid and will yield Dense Associative Memory. However, because traditional Transformers use a ReLU activation, we use a rectified quadratic energy.

ET in code

Let’s implement the attention energy in code. We will use jax and equinox for our code.

Necessary imports

import jax, jax.numpy as jnp, jax.random as jr, jax.tree_util as jtu, jax.lax as lax

import equinox as eqx

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import *

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import imageio.v2 as imageio

from glob import glob

from fastcore.basics import *

from fastcore.meta import *

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from jaxtyping import Float, Array

import functools as ft

from einops import rearrange

from amtutorial.data_utils import get_et_imgs, get_et_checkpointThe EnergyTransformer class captures all the token processing in the entire transformer. There are maybe 7 lines of code that perform the actual energy computation. This single energy function, when paired with a layer-norm, is analogous to the full computation across all layers of a traditional transformer. The only things missing are some some token and position embedding matrices to make it work on real data, but we will do that in the following section.

First, let’s describe the configuration for ET:

class ETConfig(eqx.Module):

D: int = 768 # token dimension

H: int = 12 # number of heads

Y: int = 64 # head dimension

M: int = 3072 # MLP size

beta: Optional[float] = None # Inverse temperature for attention, defaults to 1/sqrt(Y)

prevent_self_attention: bool = True # Prevent explicit self-attention

def get_beta(self): return self.beta or 1/jnp.sqrt(self.Y)

smallETConfig = ETConfig(D=12, H=2, Y=6, M=24)

mediumETConfig = ETConfig(D=128, H=4, Y=32, M=256)

fullETConfig = ETConfig(D=768, H=12, Y=64, M=3072, beta=1/jnp.sqrt(64))The ETConfig class captures all the dimensions and default hyperparameters for ET. The only thing left to do is implement the energies of Energy Transformer

class EnergyTransformer(eqx.Module):

config: ETConfig

Wq: Float[Array, "H D Y"] # Query projection

Wk: Float[Array, "H D Y"] # Key projection

Xi: Float[Array, "M D"]EnergyTransformer is parameterized by only three matrices: \(\mathbf{W}^Q, \mathbf{W}^K\) and \(\mathbf{Xi}\) (we did not choose to introduce any biases, though we could have).

We use these parameters to define both the attention energy and the memory energy.

@patch

def attn_energy(self: EnergyTransformer, xhat: Float[Array, "N D"]):

beta = self.config.get_beta()

K = jnp.einsum("kd,hdy->khy", xhat, self.Wk)

Q = jnp.einsum("qd,hdy->qhy", xhat, self.Wq)

N = K.shape[0]

if self.config.prevent_self_attention:

bmask = jnp.ones((N, N)) - jnp.eye(N) # Prevent self-attention

else:

bmask = jnp.ones((N, N))

A = jax.nn.logsumexp(beta * jnp.einsum("khy,qhy->hqk", K, Q), b=bmask, axis=-1)

return -1/beta * A.sum()

@patch

def hn_energy(self: EnergyTransformer, xhat: Float[Array, "N D"]):

"""ReLU-based "memory energy" using a Hopfield Network"""

hid = jnp.einsum("nd,md->nm", xhat, self.Xi)

return -0.5 * (hid.clip(0) ** 2).sum()The total energy is just the sum of the attention and memory energies.

@patch

def energy(self: EnergyTransformer, xhat: Float[Array, "N D"]):

"Total energy of the Energy Transformer"

return self.attn_energy(xhat) + self.hn_energy(xhat)And finally, let’s make a classmethod to easily initialize the module with random parameters.

@patch(cls_method=True)

def rand_init(cls: EnergyTransformer, key, config: ETConfig):

key1, key2, key3 = jr.split(key, 3)

return cls(config,

Wq=jr.normal(key1, (config.H, config.D, config.Y)) / jnp.sqrt(config.Y),

Wk=jr.normal(key2, (config.H, config.D, config.Y)) / jnp.sqrt(config.Y),

Xi=jr.normal(key3, (config.M, config.D)) / jnp.sqrt(config.D)

)Note that the xhat inputs above are all layer-normalized tokens. However, like other AMs, we restrict ourselves to using non-linearities that are gradients of a convex Lagrangian function. Our “special layernorm” is the same as the standard layer normalization except that we need our learnable gamma parameter to be a scalar instead of a vector of shape D. We will just show this in code below.

class EnergyLayerNorm(eqx.Module):

"""Define our primary activation function (modified LayerNorm) as a lagrangian with energy"""

gamma: Float[Array, ""] # Scaling scalar

delta: Float[Array, "D"] # Bias per token

use_bias: bool = False

eps: float = 1e-5

def lagrangian(self, x):

"""Integral of the standard LayerNorm"""

D = x.shape[-1]

xmeaned = x - x.mean(-1, keepdims=True)

t1 = D * self.gamma * jnp.sqrt((1 / D * xmeaned**2).sum() + self.eps)

if not self.use_bias: return t1

t2 = (self.delta * x).sum()

return t1 + t2

def __call__(self, x):

"""LayerNorm. The derivative of the Lagrangian"""

xmeaned = x - x.mean(-1, keepdims=True)

v = self.gamma * (xmeaned) / jnp.sqrt((xmeaned**2).mean(-1, keepdims=True)+ self.eps)

if self.use_bias: return v + self.delta

return vThat’s it! We rely on autograd to do the energy minimization, or the “inference” pass through the entire transformer.

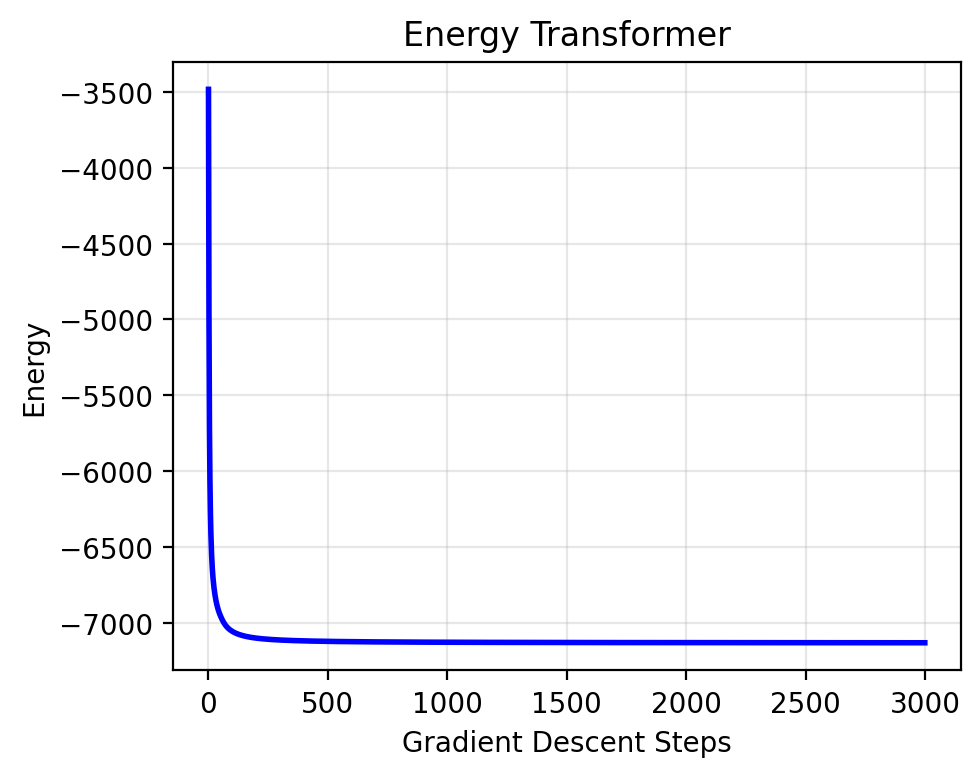

Let’s check that the energy both monotonically decreases and is bounded from below.

key = jr.PRNGKey(11)

et = EnergyTransformer.rand_init(key, config=smallETConfig)

lnorm = EnergyLayerNorm(gamma=1., delta=jnp.zeros(et.config.D))

def energy_recall(Efn, x_init, nsteps, step_size):

"Simple gradient descent to recall a memory"

@jax.jit

def gd_step(x, i):

energy, grad = jax.value_and_grad(Efn)(lnorm(x))

x_next = x - step_size * grad

return x_next, energy

xhat_init = lnorm(x_init)

final_x, energy_history = jax.lax.scan(

gd_step,

xhat_init,

jnp.arange(nsteps)

)

return final_x, energy_history

x_init = jr.normal(key, (100, et.config.D)) # Layer normalized tokens

final_x, energy_history = energy_recall(et.energy, x_init, nsteps=3000, step_size=0.5)

Inference with an Energy Transformer

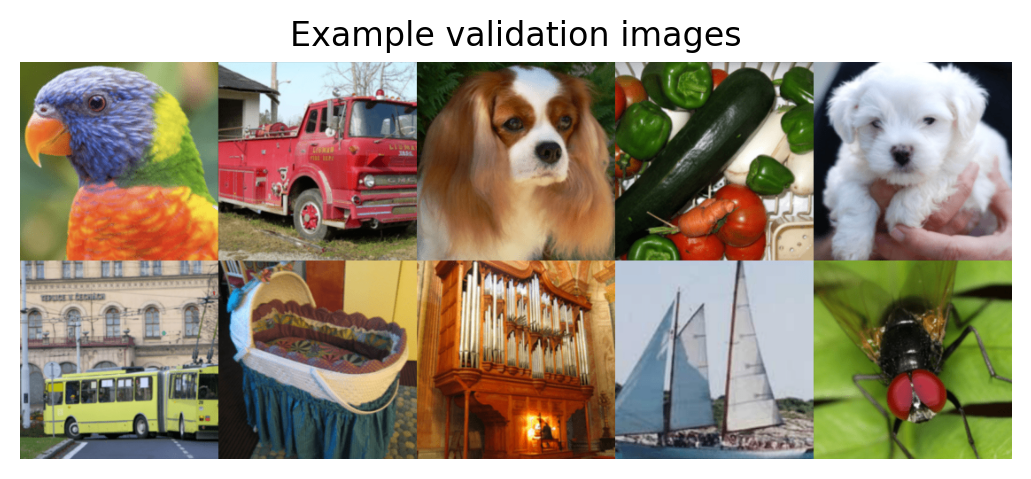

To make the Energy Transformer described above work on real data, we need to add some necessary addendums to work with image data: the token and position embedding matrices, and some data processing code.

Loading data

Energy Transformer was originally trained on ImageNet. We will load some example images (unseen during training) to demonstrate ET’s ability to remember images.

# Load and prepare unseen images

IMAGENET_MEAN = np.array([0.485, 0.456, 0.406]) * 255 # C, H, W

IMAGENET_STD = np.array([0.229, 0.224, 0.225]) * 255 # C, H, W

def normalize_img(im):

"""Put into channel first format, normalize"""

x = (im - IMAGENET_MEAN) / IMAGENET_STD

x = rearrange(x, "h w c-> c h w")

return x

def unnormalize_img(x):

"""Put back into channel last format, denormalize"""

x = rearrange(x, "c h w -> h w c")

im = (x * IMAGENET_STD) + IMAGENET_MEAN

return im.astype(jnp.uint8)

@ft.lru_cache

def get_normalized_imgs():

imgs = jnp.array(get_et_imgs())

imgs = jax.vmap(normalize_img)(imgs)

return imgs

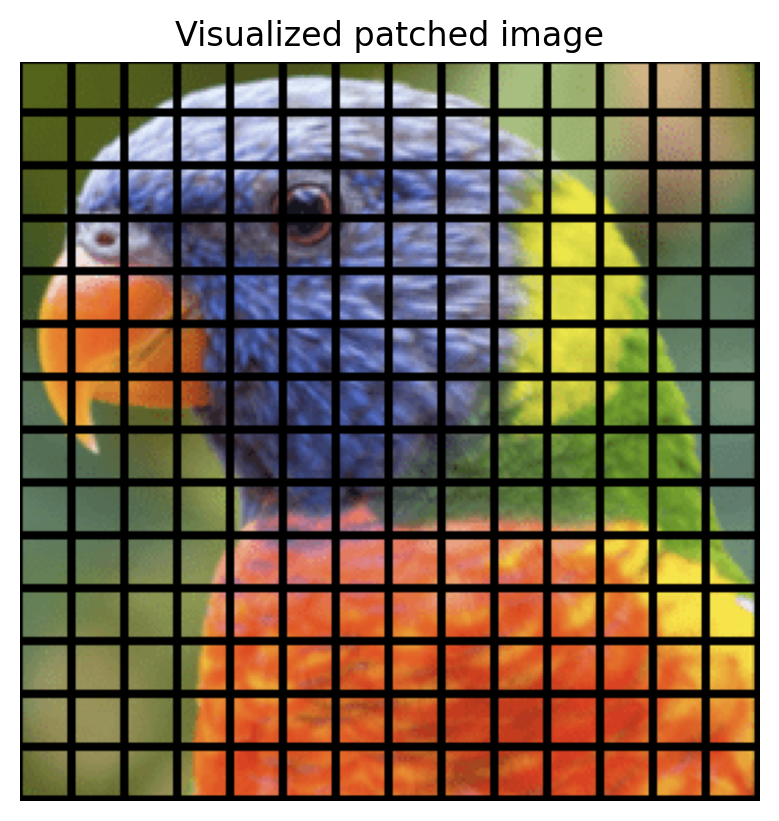

Patching images

We build a Patcher class to patchify and unpatchify images, which is mostly a simple wrapper around the rearrange function from einops.

Patcher class

class Patcher(eqx.Module):

"Patchify and unpatchify an image."

image_shape: Iterable[int] # (C, H, W) Image shape

patch_size: int # Square patch size

kh: int # Number of patches in the height direction

kw: int # Number of patches in the width direction

@property

def patch_shape(self): return (self.image_shape[0], self.patch_size, self.patch_size)

@property

def num_patch_elements(self): return ft.reduce(lambda a, b=1: a * b, self.patch_shape)

@property

def num_patches(self): return self.kh * self.kw

def patchify(self, img):

"Turn an image (possibly batched) into a collection of patches."

return rearrange(

img,

"... c (kh h) (kw w)-> ... (kh kw) c h w",

h=self.patch_size,

w=self.patch_size,

)

def unpatchify(self, patches):

"Turn a collection of patches (possibly batched) back into an image."

return rearrange(

patches, "... (kh kw) c h w -> ... c (kh h) (kw w)", kh=self.kh, kw=self.kw

)

def rasterize(self, patches):

"Rasterize patches into tokens"

return rearrange(patches, "... c h w -> ... (c h w)")

def unrasterize(self, tokens):

"Unrasterize tokens into patches"

c,h,w = self.patch_shape

return rearrange(tokens, "... (c h w) -> ... c h w", c=c, h=h, w=w)

def tokenify(self, img):

"Turn img into rasterized patches"

return self.rasterize(self.patchify(img))

def untokenify(self, tokens):

"Untokenify tokens into original image"

return self.unpatchify(self.unrasterize(tokens))

def patchified_shape(self):

"The expected shape of a patchified image"

return (self.num_patches, *self.patch_shape)

@classmethod

def from_img(cls, img, patch_size):

"Create a Patcher from an example image."

return cls.from_img_shape(img.shape, patch_size)

@classmethod

def from_img_shape(cls, img_shape, patch_size):

"Create a patcher from a specified image shape."

height, width = img_shape[-2:]

assert (height % patch_size) == 0

assert (width % patch_size) == 0

kh = int(height / patch_size)

kw = int(width / patch_size)

return cls(img_shape, patch_size, kh, kw)It lets us do things like:

patcher = Patcher.from_img_shape(imgs[0].shape, patch_size=16)

patched_img = patcher.patchify(imgs[0])

print(patched_img.shape)(196, 3, 16, 16)RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in cast

return im.astype(jnp.uint8)

Patcher.unpatchify gets us back to the original image.

assert jnp.all(patcher.unpatchify(patched_img) == imgs[0])We can also process an images and batches of imags into tokens and back.

tokenified_img = patcher.tokenify(imgs[0])

print("Token pre-embedding shape: ", tokenified_img.shape)

untokenified_img = patcher.untokenify(tokenified_img)

assert jnp.all(untokenified_img == imgs[0])

batch_tokenified_imgs = patcher.tokenify(imgs)

print("Batch token pre-embedding shape: ", batch_tokenified_imgs.shape)

batch_untokenified_imgs = patcher.untokenify(batch_tokenified_imgs)

assert jnp.all(batch_untokenified_imgs == imgs)Token pre-embedding shape: (196, 768)

Batch token pre-embedding shape: (11, 196, 768)Image-compatible ET

Let’s create a full ET, complete with embeddings, model that can be used for masked-image inpainting. We say that each image has \(N\) total patches/tokens, where each patch as \(Z = c \times h \times w\) pixels when rasterized. We will use linear embeddings (with biases) to embed and unembed rasterized image patches to tokens.

First, let’s describe the data and ET we are working with.

class ImageETConfig(eqx.Module):

image_shape: Tuple[int, int, int] = (3, 224, 224) # (C, H, W) Image shape

patch_size: int = 16 # Square patch size

et_conf: ETConfig = fullETConfigTo work with data, we add a few extra matrices: embedding/unembedding matrices (let’s use a bias for each), position embeddings, and CLS/MASK tokens. The position embeddings are used to encode the position of each token in the sequence, and the CLS/MASK tokens are used for interop with the original ViT. [2] Additionally, the layernorm is external to the computation of the ET so we’ll insert those parameters here.

class ImageEnergyTransformer(eqx.Module):

patcher: Patcher

W_emb: Float[Array, "Z D"]

b_emb: Float[Array, "D"]

W_unemb: Float[Array, "D Z"]

b_unemb: Float[Array, "Z"]

pos_embed: Float[Array, "(N+1) D"] # Don't forget the CLS token!

cls_token: jax.Array

mask_token: jax.Array

et: EnergyTransformer

lnorm: EnergyLayerNorm

config: ImageETConfigLet’s define some functions for converting image patches to/from tokens. These are a.k.a. “embedding” and “unembedding” operations.

@patch

def encode(

self: ImageEnergyTransformer,

x: Float[Array, "N Z"]

):

"Embed rasterized patches to tokens"

out = x @ self.W_emb + self.b_emb # (..., N, D)

return out

@patch

def decode(

self: ImageEnergyTransformer,

x: Float[Array, "N D"]):

"Turn x from tokens to rasterized img patches"

return x @ self.W_unemb + self.b_unemb # (..., N, Z)Masking tokens is also a part of this data connection. Let’s corrupt and add the CLS register:

@patch

def corrupt_tokens(

self: ImageEnergyTransformer,

x: Float[Array, "N D"],

mask: Float[Array, "N"],

max_n_masked: int=100):

"""Corrupt tokens with MASK tokens wherever `mask` is 1.

`max_n_masked` needs to be known in advance for JAX JIT to work properly

"""

maskmask = jnp.nonzero(mask == 1, size=max_n_masked, fill_value=0)

return x.at[maskmask].set(self.mask_token) # (..., N, D)

@patch

def prep_tokens(

self: ImageEnergyTransformer,

x: Float[Array, "N D"],

mask: Float[Array, "N"]):

"Add CLS+MASK tokens and POS embeddings"

x = self.corrupt_tokens(x, mask)

x = jnp.concatenate([self.cls_token[None], x]) # (..., N+1, D)

return x + self.pos_embed # (..., N+1, D)The inference process is gradient descent down the energy, and turns a full image whose patches are masked according to mask and returns predictions for the whole image.

@patch

def __call__(

self: ImageEnergyTransformer,

img: Float[Array, "C H W"],

mask: Float[Array, "N"],

nsteps=12,

step_size=0.1):

"A complete pipeline for masked image modeling in ET using gradient descent"

x = self.patcher.tokenify(img) # (..., N, Z)

x = self.encode(x)

x = self.prep_tokens(x, mask) # (..., N+1, D)

get_energy_info = jax.value_and_grad(self.et.energy)

def gd_step(x, i):

xhat = self.lnorm(x)

E, dEdg = get_energy_info(xhat)

x_next = x - step_size * dEdg

return x_next, {"energy": E, "xhat": xhat}

x, traj_outputs = jax.lax.scan(gd_step, x, jnp.arange(nsteps))

xhat_final = self.lnorm(x)

E_final = self.et.energy(xhat_final)

traj_outputs['xhat'] = jnp.concatenate([traj_outputs['xhat'], xhat_final[None]], axis=0)

traj_outputs['energy'] = jnp.concatenate([traj_outputs['energy'], E_final[None]], axis=0)

xhat_final = xhat_final[1:] # Discard CLS token for masked inpainting

x_decoded = self.decode(xhat_final)

return self.patcher.untokenify(x_decoded), traj_outputsFor completeness, let’s add a helper function to initialize the model with random parameters. We won’t use it in this tutorial, however.

@patch(cls_method=True)

def rand_init(cls: ImageEnergyTransformer, key, config=ImageETConfig()):

key1, key2, key3, key4, key5, key6, key7, key8 = jr.split(key, 8)

patcher = Patcher.from_img_shape(config.image_shape, config.patch_size)

W_emb = jr.normal(key1, (patcher.num_patch_elements, config.et_conf.D)) / config.et_conf.D

b_emb = jr.normal(key2, (config.et_conf.D,))

W_unemb = jr.normal(key3, (config.et_conf.D, patcher.num_patch_elements)) / patcher.num_patch_elements

b_unemb = jr.normal(key4, (patcher.num_patch_elements,))

pos_embed = jr.normal(key5, (patcher.num_patches, config.et_conf.D)) / config.et_conf.D

cls_token = 0.002 * jr.normal(key6, (config.et_conf.D,))

mask_token = 0.002 * jr.normal(key7, (config.et_conf.D,))

pos_embed = 0.002 * jr.normal(key8, (1 + patcher.num_patches, config.et_conf.D)) / config.et_conf.D

return cls(

patcher=patcher,

W_emb=W_emb,

b_emb=b_emb,

W_unemb=W_unemb,

b_unemb=b_unemb,

pos_embed=pos_embed,

cls_token=cls_token,

mask_token=mask_token,

et=EnergyTransformer.rand_init(key7, config.et_conf),

lnorm=EnergyLayerNorm(gamma=1., delta=jnp.zeros(config.et_conf.D)),

config=config

)

imageET = ImageEnergyTransformer.rand_init(key, ImageETConfig())Loading pretrained weights

ET has publicly available pretrained weights that can be used for masked-image inpainting. The model itself is pretty small ~20MB, with no compression tricks on the weights (everything is np.float32). We load the state dict from a saved .npz file as follows:

@ft.lru_cache

def get_pretrained_et():

load_dict = {k: jnp.array(v) for k,v in get_et_checkpoint().items()}

# config from state_dict

H, Y, D = load_dict["Wk"].shape

D, M = load_dict["Xi"].shape

et_config = ETConfig(D=D, H=H, Y=Y, M=M, prevent_self_attention=False) # These weights were trained allowing self attention. But the arch works equally well both ways.

et = EnergyTransformer(

Wk = rearrange(load_dict["Wk"], "h y d -> h d y"),

Wq = rearrange(load_dict["Wq"], "h y d -> h d y"),

Xi = rearrange(load_dict["Xi"], "d m -> m d"),

config = et_config

)

image_config = ImageETConfig(image_shape=(3, 224, 224), patch_size=16, et_conf=et_config)

patcher = Patcher.from_img_shape(image_config.image_shape, image_config.patch_size)

iet = ImageEnergyTransformer(

patcher = patcher,

W_emb = load_dict["Wenc"],

b_emb = load_dict["Benc"],

W_unemb = load_dict["Wdec"],

b_unemb = load_dict["Bdec"],

pos_embed = load_dict["POS_embed"],

cls_token = load_dict["CLS_token"],

mask_token = load_dict["MASK_token"],

et = et,

lnorm = EnergyLayerNorm(gamma=load_dict["LNORM_gamma"], delta=load_dict["LNORM_bias"]),

config = image_config

)

return ietWe can inpaint images with ET.

def inpaint_image(

iet: ImageEnergyTransformer,

img: Float[Array, "C H W"],

n_mask: int,

key: jax.random.PRNGKey,

nsteps: int=12,

step_size: float=0.1):

" Perform masked image inpainting with Energy Transformer"

# Create random mask

mask_idxs = jr.choice(

key, np.arange(iet.patcher.num_patches), shape=(n_mask,), replace=False

)

mask = jnp.zeros(iet.patcher.num_patches).at[mask_idxs].set(1)

x = iet.patcher.tokenify(img)

x = iet.encode(x) # Img to embedded tokens

x = iet.prep_tokens(x, mask)[1:] # N,D (remove CLS token)

masked_img = iet.decode(iet.lnorm(x))

masked_img = iet.patcher.untokenify(masked_img)

# Reconstruct image using Energy Transformer

recons_img, traj_outputs = iet(img, mask, nsteps=nsteps, step_size=step_size)

return masked_img, recons_img, traj_outputs

iet = get_pretrained_et()

nh, nw = 2, 5

N = nh*nw

og_imgs = get_normalized_imgs()[:N]

keys = jr.split(jr.PRNGKey(0), len(og_imgs))

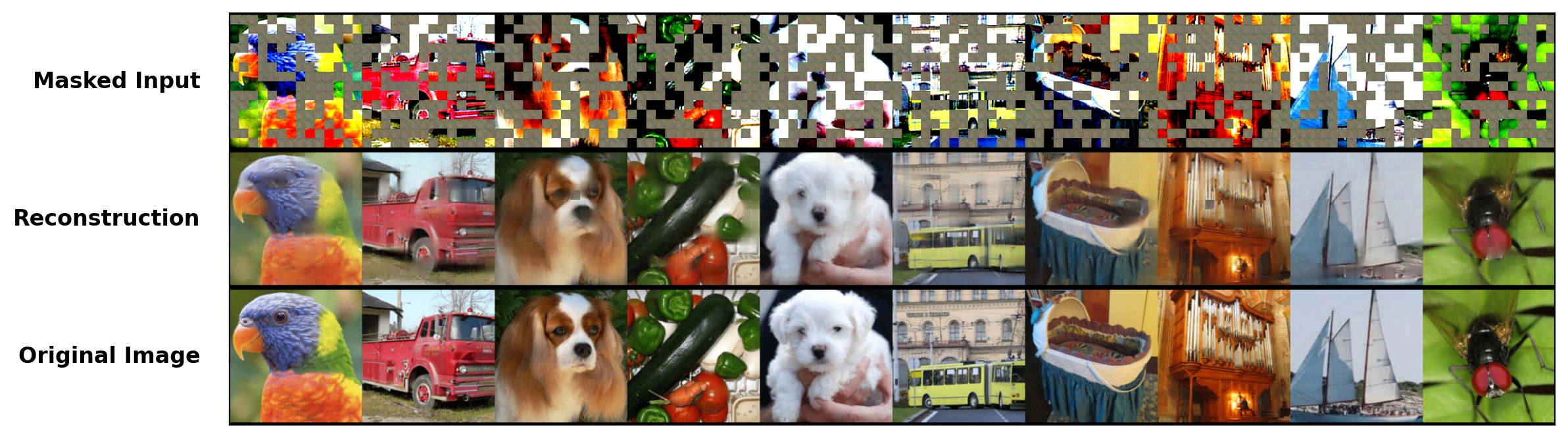

masked_imgs, recons_imgs, traj_outputs = jax.vmap(inpaint_image, in_axes=(None, 0, None, 0))(iet, og_imgs, 100, keys)

vunnormalize_img = jax.vmap(unnormalize_img)

og_imgs_show, masked_imgs_show, recons_imgs_show = [vunnormalize_img(im) for im in (og_imgs, masked_imgs, recons_imgs)]

We can also animate the retrieval.

Animation dependencies

from pathlib import Path

import matplotlib.animation as animation

from IPython.display import Video, Markdown

from moviepy.editor import ipython_display

import os

CACHE_DIR = Path("./cache") / "01_energy_transformer"

CACHE_DIR.mkdir(exist_ok=True, parents=True)

CACHE_VIDEOS = TrueThese images are fully reconstructed using autograd down the parameterized energy function. You may notice the reconstructions are not perfect, e.g., the right eye of the white dog is missing.

Unfortunately, these weights were only trained to 12 steps at a fixed step size. Running longer will still cause the energy to decrease, but our image reconstruction quality will not improve. This reflects that our model has learned a kind of ‘metastable state’ at which nice reconstructions are retrieved, but these reconstructions are not “memories” in the formal definition of the term.

masked_imgs, recons_imgs, traj_outputs = jax.vmap(ft.partial(inpaint_image, nsteps=40), in_axes=(None, 0, None, 0))(iet, og_imgs, 100, keys)

video, video_fname = show_et_recall_animation(iet, traj_outputs, "et_reconstruction_long",

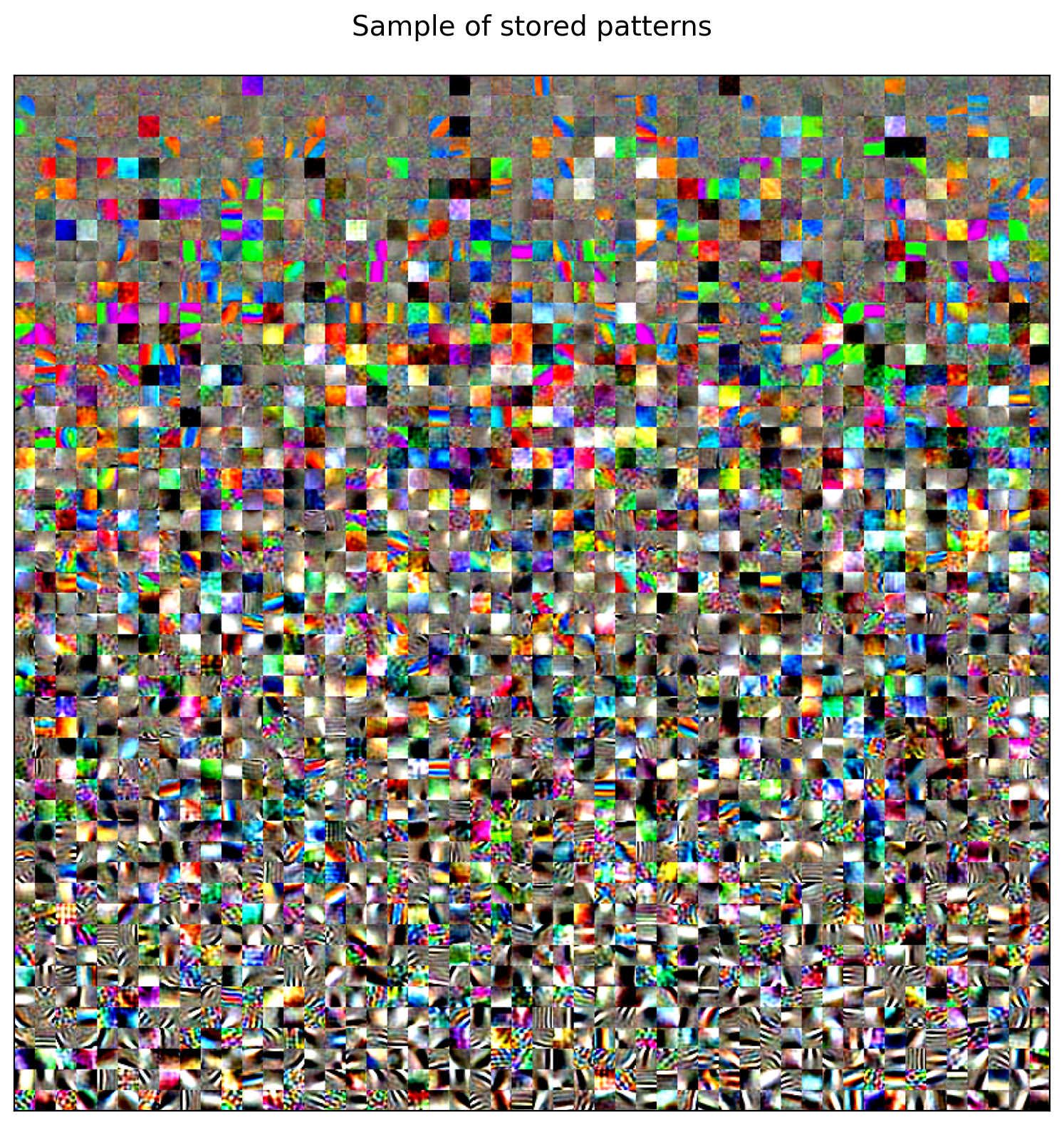

steps_per_sample=1, force_remake=True)Interpreting ET

The representations learned by ET are attractors of the dynamics. That is, the weights of the Hofield Network in ET are not arbitrary linear transformations — they are actual stored data patterns. Visualizing the weights reveals what the model has actually learned.

def decode_stored_pattern(iet, xi):

c,h,w = iet.patcher.patch_shape

decoded = iet.decode(iet.lnorm(xi))

patches = rearrange(decoded, '... (c h w) -> ... c h w', c=c, h=h, w=w)

return unnormalize_img(patches)

Xi_show = jax.vmap(ft.partial(decode_stored_pattern, iet))(iet.et.Xi)

You can think of the Hopfield Network like an SAE that is integrated into the core computation of the model. Interpretability is a natural byproduct of good architecture design.